In his recent novels, Ghostwritten (1999) and Cloud Atlas (2004), David Mitchell has taken up systems themes, which are increasingly accessible as systems theory develops and its interdisciplinary applications grow in scope. More specifically, Mitchell’s novels deal with the implications of daily global interactions between people (made possible through modern communications technology), a resultant codependence of actors within this system, and how actors must be considered in increasingly global terms, a move toward working with wholes (whole systems) rather then parts (individual actors). These aspects contribute to an exploration in the novel of the human position within a global environment, as well as human impacts like environmental change and possible eventual apocalypse. In Ghostwritten, Mitchell creates an intricate picture of the global network. Ghostwritten reads like a series of very loosely related short stories. Each of the ten chapters is set in a different place, typically at an unspecified time in relation to the other chapters, and features a different narrator or protagonist. During the course of the novel, certain repeated patterns and motifs become apparent, but the larger structure of complex interconnections is not visible until the novel’s conclusion. In this way, Mitchell illustrates precisely the kind of method adopted by systems theorists: the novel must be viewed as a whole, rather than piecemeal, in order to understand the story. A systems theoretical approach to the novel facilitates this type of analysis.

In A Strategy for the Future (1974), Ervin Laszlo, a philosopher of science and systems theorist, proposes that a general systems view of the world is necessary if we are to avoid global catastrophe as a result of human-induced imbalances in the global system. Laszlo asserts, “The system level of analysis permits one to examine international relations as a whole…The advantages of the world system level reside in the comprehensiveness of the analysis and the perception of patterns otherwise lost in the maze of data.” [3] The emphasis on wholeness and global pattern discernment, rather than stopping at local analyses, is key to Laszlo’s view and fairly intuitive given the increasing interdependence of nations and communities in a worldwide economy. However, there are limitations to this approach. While systems theory has the advantage of comprehensive analysis, it necessarily elides detailed features of the system being studied, retaining only a select few characteristic elements. A suitable analogy from literary studies might be a formal analysis with a small selection of close readings versus a detailed close reading.

Ludwig von Bertalanffy, in his seminal text, General System Theory (1968), describes the systems problem as “essentially the problem of the limitations of analytical procedures in science. […] ‘Analytical procedure’ means that an entity investigated be resolved into, and hence can be constituted or reconstituted from, the parts put together, these procedures being understood both in their material and conceptual sense.” [4] In this definition, a systems theoretical approach can offer a scientific account of the cliché that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Laszlo adds, “[Groups of interacting parts] exhibit a certain uniqueness of characteristics as wholes. They cannot simply be reduced to the properties of their individual parts.” [5] Even with the extreme specialization that has occurred recently in science, science still cannot deal with systems containing many particles, and certainly not systems in which the parts interact and cannot be reduced to basic principles. [6] Where traditional science examines components and builds up from that foundation, utilizing a complex systems model permits both bottom-up and top-down approaches. This multiplicity of approaches is necessary here for dealing with complex nonlinearities, situations in which system inputs do not have a direct or predictable correlation with outputs, and emergent phenomena, global characteristics that cannot be accounted for in the properties of the constituent components.

Supplementing Bertalanffy’s and Laszlo’s definitions, one can briefly summarize complex systems as possessing several basic characteristics. In Modeling Complex Systems (2004), Nino Boccara lists these characteristics as the essential traits of complex systems:

- They consist of a large number of interacting agents.

- They exhibit emergence; that is, a self-organizing collective behavior difficult to anticipate from the knowledge of the agents' behavior.

- Their emergent behavior does not result from the existence of a central controller. [7]

In literary terms, there must be many interconnected, interacting components, chapters or individual characters. The overall organization must be a result not simply of the agents’ behavior or plot movements, but also of their interactions. Last, there is, within the system or text, no central controlling agent. Instead of following a main protagonist through the narrative and experiencing the storyline as a result of his or her actions, the action is undertaken by a group of agents or characters.

Modeling Ghostwritten as a complex system, in particular a complex network of interacting agents, facilitates an analysis of the individual chapters (nodes in a network, perhaps) while preserving the bigger picture and its resulting emergent properties. In this context I mean “modeling” in the sense of figuring the novel, or in fact any system, as a graphical representation of its essential form. Indeed, later in this essay I will present network diagrams representing Ghostwritten. Similarly, here I am using the phrase “complex network” to refer to the presence of causally unpredictable effects on and relationships with later chapters.

Working through Ghostwritten from a systems perspective reveals a networked and evolving pattern of interconnections between locations and agents (both human and non-human*), as well as a variety of views on fate versus chance (especially the fate of the world), and the position of humankind with respect to its own fate and its responsibility for the fate of the global environment. A kind of musical repetition of phrases and image patterns also builds through the almost operatic construction of repeated motifs. Ghostwritten is a tapestry that requires attention to detail, an eye for pattern, and a good ear. Throughout, the apocalyptic rhetoric is woven in staging the debate between fate and chance, as well as between science, technology and nature.

Utilizing a circular structure, Ghostwritten opens as it will close: “Who was blowing on the nape of my neck?” [8] The setting is Okinawa, and the narrator is a member of a doomsday cult, the Fellowship, who calls himself Quasar. Despite the lack of credibility associated with his cult member status, Quasar’s position on the environment and his intentions for the future of the world are strangely noble. Quasar laments the current state of Japan and the world at large and looks forward to the cleansing of man:

Dazzling the unclean into compliance. The urban districts, the factories pumping out poison into the air and water supplies. Fridges abandoned in wastegrounds of lesser trash. What grafted-on pieces of ugliness are their cities! I imagine the New Earth sweeping this festering mess away like a mighty broom, returning the land to its virginal state.[9]

Though he does not identify himself with the earth to the extent that later narrators do (for example, the woman living in her tea shack on Holy Mountain in chapter four), Quasar recognizes the “zombifying” effect of uniform urban sprawl, its ugliness and pollution. Even a labeled terrorist can see that such a divorce from the earth cannot be sustained. Thus, when the Fellowship cult attacks the subways, Quasar wants to view it as a gift, an early release from misery both present and future. However, he can no more escape the guilt than he can escape the ever-present filth of worldwide commerce and shopping malls. Even far out on an island off the coast of Okinawa, Quasar sees the face of a child on the subway he bombed. Against environmental aims (albeit religiously skewed ones), the conflict between environmental and human justice remains. Quasar suffers from operating within a system that inescapably links him with other “unclean” people.

Beyond the environmental implications, though Quasar cannot see it, the reader, moving to the next chapter, quickly realizes that Quasar’s purpose, at least part of it, is to alter the life of the next narrator, a young man named Satoru. Though there are plenty of recurring motifs throughout the second chapter, the first connection is fairly straightforward, as though Mitchell is teaching his audience the game his novel will play. In chapter one, “Okinawa,” Quasar makes a call saying, “The dog needs to be fed,”[10] which Satoru receives by mistake in the record shop where he works in Tokyo.

Though Satoru and Quasar thus share what I will term a direct link in the novel through the connection of the phone call, they present two very different vantage points on the global ecosystem. Quasar running to the edge of the world to escape his crimes cannot achieve the kind of isolation Satoru does in his own mind in the midst of bustling Tokyo. Considering the mass and noise of the city, Satoru notes, “Twenty million people live and work in Tokyo. It’s so big that nobody really knows where it stops. It’s long since filled up the plain, and now it’s creeping up the mountains to the west and reclaiming land from the bay in the east.”[11] Despite this somewhat horrifying example of urban sprawl, exactly the type abhorred by Quasar, Satoru claims, “The city is vast, but there’s always someone who knows someone whom someone knows.”[12] Highlighting the network of social interactions available in the city, amazingly, the human connection is not lost amid the crush. Satoru does not seem to have strong negative opinions on the sprawl; for him it is simply a fact of the Tokyo ecosystem. Satoru instead emphasizes the kind of adaptation necessary for denizens of the ecosystem to survive. The succeeding chapter, set in Hong Kong, similarly deals with the need to escape the city center, sever all ties, and find a place of peace.

Moving forward in the novel to chapter five, “Mongolia,” perhaps the most interesting narrator is known only as a noncorpum, a spirit being that can move from host to host, a kind of benign parasite seeking only knowledge of its own origins. Though it has no physical body, the noncorpum cares about the fate of the world; it is a “nonhuman humanist.”[13] Thinking of humans and the state of the world, the noncorpum says, “Humans live in a pit of cheating, exploiting, hurting, incarcerating. Every time, the species wastes some part of what it could be. This waste is poisonous. That is why I no longer harm my hosts. There’s already too much of this poison.”[14] Just as Quasar did, the noncorpum sees the toxic waste and destructive nature of man, though the noncorpum deals more in mental depravity since his home is in his host’s mind. The idea that human inhumanity is polluting and destroying the planet presents an interesting complement to the more traditional environmental focus on the destruction of the non-living, or at least non-human, portion of the global ecosystem, rather than the system as a whole.

Though system theory admittedly was not formulated with the aim of applying it to novels, Mitchell's Ghostwritten can thus be read as an example of a complex system that itself deals with a nested complex system, the global ecosystem. In keeping with the criteria listed above, the chapters as well as the characters in them work as interacting agents locally, and they produce global behavior (the overall plot, the novel itself) without the connective thread of any common, central agent within the novel. Bertalanffy explicitly makes room for the theory’s application to areas other than hard science; he says, “Models in ordinary language therefore have their place in systems theory. The system idea retains its value even where it cannot be formulated mathematically, or remains a ‘guiding idea’ rather than being a mathematical construct.”[15] Even against potential limitations of the use of system theory on language-based models, I suggest that the novel, in addition to being admissible in a systems approach as a model in words, also acts as a representation of a physical system. Ghostwritten in particular offers a possible version of the future state of the global ecosystem under the influence of human poisoning and urban sprawl. Further, Ghostwritten illustrates real complex behavior; because of this, Mitchell’s fictional universe can be analyzed in the same way that any other physical system can be. It is also worth noting here that, because systems theory allows for a multiplicity of simultaneous interpretations, one could use modeling techniques other than the network model that I will be employing later in reference to Ghostwritten.

Deploying the underlying assumption of systems theory, Mitchell emphasizes the interconnectedness of agents in an open global system. Bertalanffy describes open systems: “An open system is defined as a system in exchange of matter with its environment…open systems can maintain themselves in a state of high statistical improbability, of order and organization” without violating the laws of thermodynamics.[16] In short, dynamic interactions between parts along with their interaction with the environment can lead to the potential for increasing complexity.[17] Where closed systems are subject to decay due to accordance with the second law of thermodynamics, open systems may increase in order and complexity. The network in Ghostwritten evolves as chapters and nodes are added, importing information from the novel’s fictional universe and productively complicating the reading experience. Mitchell’s system is especially rich in its emphasis on human-environment interaction: characters are often linked in space, if not in time, and linked in their similar thoughts about particular places and spaces.

Considering this human-environment interaction in terms of ecosystems, themselves subject to complex systems modeling, adds another layer to Mitchell’s web. According to Laszlo, “Ecosystems [are] the integration of the communities of living organisms and their total nonliving environment in a geographical region of the earth at a particular point in time. The basic units are the individual living organisms. They form the nodal points of a network enmeshed in, and integrated with, the environmental matrix.”[18] In Mitchell’s global system, which aligns nicely with this ecosystem model, in structure as well as in the thematic environmental concerns discussed earlier, living entities (the characters in the novel) are constantly bombarded with new information as a result of random choices by other agents or characters or from environmental pressures. The image of the dynamic network or matrix here is also particularly apt. Ghostwritten models as a web, which, like the environment, falls into decay, rather than continuously evolving, if a static state is reached. Without dynamically changing the inputs and the relationships between nodes, the system fails.

Leading to these dynamic changes, seemingly trivial actions by characters in different sections of the book set in different parts of the world may cause catastrophic results for other apparently unconnected characters. Examining the structure of Ghostwritten illustrates that disjoint elements in space and time can stand alone when viewed individually but work together to render larger patterns when viewed as a whole. In the constantly shifting dynamic system depicted in the novel, apparently unrelated series of events hide a pattern that does not become visible until the reader is already familiar with the novel, perhaps even until the novel’s conclusion. If that is the case, then the pattern becomes a matter of perspective. Daniel Dennett, philosopher of science and the mind, suggests, “Other creatures with different sense organs, or different interests, might readily perceive patterns that were imperceptible to us. The patterns would be there all along, but just invisible to us.”[19] While the pattern is certainly real before it becomes discernable, for Ghostwritten it does not impact the reading process until it appears. The question one must then ask is, “But how could the order be there, so visible amidst the noise, if it were not the direct outline of a concrete orderly process in the background?”[20] To this, Dennett suggests that the pattern is, instead of some overarching theme or motif, rather a collection of small parts that contribute to the pattern.[21] In Mitchell’s individual chapters, the parts that make up his larger organized structure are not noticeable because they are not central to the story, indeed there is no central story, but, by the novel’s end, the overall picture is visible nevertheless, an accumulation of related details.

Almost immediately after receiving Quasar’s call, linking chapters one and two, Satoru identifies this as a pivotal, perhaps fated, moment in his life. He says, “I’ve thought about it many times since: if that phone hadn’t rung at that moment, and if I hadn’t taken the decision to go back and answer it, then everything that happened afterwards wouldn’t have happened.”[22] Satoru expresses here the sense of cohesion achieved at the conclusion of Ghostwritten, echoing the whole within a single part, in his belief in the idea that everything that happened was part of a fated design. However, though what he says is true, changing his decision to answer the phone would have changed his life and perhaps he would not have met Tomoyo, it is also equally true that taking the other decision would have irrevocably changed his life. Perhaps he would have been hit by a bus, or won the lottery. Because the story is not Satoru’s, the reader does not find out what happens later in time. What Satoru identifies as amazing luck or fate could have been neither. Satoru alludes briefly to the thought that it might the hand of God, or of God’s ghostwriter: “For a moment I had an odd sensation of being in a story that someone was writing, but soon that sensation too was being swallowed up.”[23] Even amid his delight at the fated phone call, fate is the stuff of the imagination, of fairy tales and fiction. This moment also seems a direct signal to the reader to consider that Satoru is exactly right—he is in a story that someone is writing, implying that this sort of thing does not really happen.

The narrator of “Hong Kong,” Neal Brose, is a slave to his job; he opens the chapter having nightmares about computers, which re-emphasizes the motif of inescapable connectedness through modern communication systems.[24] Like Satoru, Neal wonders how different his life would have been if he had gone for the woman he loves: “She turned and walked away, and I sometimes wonder, had I run back to her, could we have found ourselves pin-balled into an altogether different universe, or would I have just got my nose broken? I never found out. I obeyed the ferry bell.”[25] Both Neal and Satoru are linked to technology; they both obey the ringing bell, and they wonder about the alternatives to not listening. Where Satoru can find refuge in the city, Neal cannot. Oddly, the link between these chapters is the direct one of Neal watching Satoru with his girlfriend at a hamburger joint and wishing he could trade places, trade lives.[26]

Examining how his life came to be the way it is, Neal Brose, the narrator of chapter three, ponders the nature of the global system in which he is enmeshed:

Or is it not a question of cause and effect, but a question of wholeness? I’m this person, I’m this person, I’m that person, I’m that person too. No wonder it’s all such a fucking mess. I divided up my possible futures, put them into separate accounts, and now they’re all spent. Big thoughts for a bent little lawyer.[27]

Here Neal captures interesting features of systems that resonate throughout Ghostwritten. His focus on wholeness coupled with the emphasis on a collection of individuals mirrors the network or systems approach taken in the novel. Each part is vital, though no single component can generate the global picture. Nonetheless, sacrificing any of them, as he claims to have done, carving them up and spending them, detracts from the overall system. The parts are all connected and necessary to the whole system.

Though the noncorpum does seem to care about humanity for its own sake, as I discussed earlier, its primary objective is to discover the origin of itself, which it remembers nothing about except for one myth: “There are three who think about the fate of the world.”[28] These three are all flying animals. First, the crane steps lightly for fear that “the mountains will collapse and the ground will quiver and trees that have stood for a thousand years will tumble.”[29] Next, the locust fears “that one day the flood will come and deluge the world…That is why the locust keeps such a watchful eye on the high peaks, and the rain clouds that might be gathering there. Third, the bat. The bat believes that the sky may fall and shatter…That was the story, way back at the beginning.”[30] The motif of flying animals permeates Ghostwritten. The bat in particular is ubiquitous. In this sense, strangely, the noncorpum’s quest that would ultimately disconnect it from beings around it, by returning it to its origins, works as a connective device in Ghostwritten. Characters who are described as “blind as bat” are the ones that can see best (for example, John Cullin, the husband of chapter eight’s narrator). Perhaps the most important instance of the bat comes in the penultimate chapter, which is narrated by Bat Segundo, a radio deejay in New York. While this image links the various chapters (almost all contain a bat reference), the link is fleeting and undetectable if one were to read the chapters individually. The importance of the bat is thus an example of emergent phenomena arising from global connections as well as a motif signifying the need to attend to the fate of the global environment.

Related to the idea of elaborate interconnectivity, a general concern with unpredictable cause and effect as potentially leading to future global catastrophe or upheaval pervades the novel. Bertalanffy, like Laszlo, suggests that using a systems theoretical model, or at least thinking in terms of global systems when dealing with social organizations at all scales, can lead to “a well-developed science of human society and a corresponding technology, [which] would be the way out of the chaos and impending destruction of our present world.”[31] Though this hope might be realistically possible, even the development of human systems science does not preclude the possibility for a kind of Orwellian dystopia rather than a utopia. Mitchell toys with the prospect of a return to an Edenic paradise in Ghostwritten through a number of end-of-the-current-world scenarios; however, perhaps due to the extremely complex nature of his global system, all attempts at paradise fail.

In assessing the reasons behind this seemingly unavoidable global apocalypse in Ghostwritten, the ability to detect patterns out of apparent randomness comes back into play. Beyond merely making the inter-chapter and inter-character connections by the conclusion of the novel, one feels confident in thinking that clearly the apocalyptic ending was coming all along. It is taken as inevitability, an accumulation of predetermined pressures. Bertalanffy suggests similarly that inevitable historical forces shape the outcome of nonlinear processes; in particular he discusses the idea that unavoidable catastrophe is the natural product of these forces. Perhaps, “the historic process is not completely accidental but follows regularities or laws which can be determined” in the same way in which natural laws are.[32] This suggests the existence of historical repetition. The cyclic character of natural systems and maybe historical systems is represented in Ghostwritten by a return to the beginning. The final chapter takes the reader back to the first chapter, but now the reader is equipped to detect the patterns that have evolved over the course of the novel based on the repeated images and motifs. In the case of this novel, it seems that these historical forces lead directly to catastrophe. Apocalypse is apparently a product of inescapable forces, patterned and unavoidable, so why take action?

This theme of inescapable doom permeates the literature on global climate change. Everyone can see the disaster coming, but we are apparently powerless to stop it. The problem is too big, the outcomes of any action are too hard to predict or too insignificant to be meaningful, and, in any case, the issue is too vast for any one person to make a difference. This formulation underscores Mitchell’s references to the decaying planet and informs his characters attempts to affect change. However, merely the fact that a number of potential solutions, possible roads toward paradise, are offered speaks more positively than many articles on the subject of global deterioration. Formulating a model-based analysis allows Mitchell to propose a combined parts/whole solution. Whereas systems theory focuses on the whole, Mitchell’s structure draws out the agency of his individual characters while placing them in part of a larger project. This offers an answer to the issue of historical forces leading unstoppably to global apocalypse as a problem that is too big to solve.

Complicating ideas of potential global agency, beyond simply exploring the intricate links of the global network, Ghostwritten deals more explicitly with how people treat chance and fate. In the London chapter, narrated by Marco, ghostwriter and drummer for a band called “The Music of Chance,” the main character spends a considerable amount of time wondering about fate versus chance and why people do what they do. He works as a ghostwriter (another allusion within the novel to the writing process, apparently a theme of Mitchell’s) because “the endings have nothing to do with [him].”[33] This kind of purposive anonymity, staying detached for a living, is not present to such an extent elsewhere in the novel, even in the other city chapters.

Marco slides through life counting on a series of lucky dice rolls, imagining variations of causes and their rippling effects: “But why did I make that choice? Because I am me…Why am I me? … Chance, that’s why. Because of the cocktail of genetics and upbringing fixed for me by the blind barman Chance.”[34] Marco delights in chance, revels in its possibilities, “If that chair hadn’t arrived when it did, and Katy hadn’t flipped out and asked me to leave, then I wouldn’t have been at that precise spot to stop that woman being flattened. I’ve never saved anyone’s life before.”[35] Despite his extreme fascination with the potential of his various choices, Marco never really stops to consider the full impact of what he does. As his sometime girlfriend notes, “You love talking about cause. You never talk about effect.”[36] Marco goes only so far as to think about how differently a particular event could have happened, but he does not think about how he wishes it might have happened or how he might take action to initiate effects rather than stumbling over them blindly.

Though his musings on chance are in general relatively shallow, Marco as a ghostwriter himself thinks of chance and fate in book terms. Taken together with the many other direct references to imagining oneself as a character in a book (most notably Satoru from chapter two), this formulation speaks more pointedly as part of the novel’s ongoing examination of writing, fate, and their relationship to real life. Marco tells us,

The Marco Chance versus Fate Videoed Sports Match Analogy. It goes like this: when the players are out there the game is a sealed arena of interbombarding chance. But when the game is on video then every tiniest action already exists. The past, present, and future exist at the same time: all the tape is there, in your hand. There can be no chance, for every human decision and random fall of the ball is already fated. Therefore, does chance or fate control our lives? Well, the answer is as relative as time. If you’re in your life, chance. Viewed from the outside, like a book you’re reading, it’s fate all the way.[37]

Simply by reading the book, we are determining the system and reading fate into chance encounters in the universe of Ghostwritten. For the characters, Marco (Mitchell perhaps?) implies that the events are really chance, but the readers, in our desperation for pattern he practically accuses us, are unable to see that because of their out-of-system perspective. In the end it is all about perspective: “We all think we’re in control of our own lives, but really they’re pre-ghostwritten by forces around us.”[38] Again, Marco reminds the reader of the inescapable forces of history, and in a sense absolves all participants from global responsibility.

Further, whether they have any agency or not, Mitchell’s characters are unsuccessful in their aims at a new future. For example, near the end of Ghostwritten, the Zookeeper remarks,

I believed I could do much. I stabilized stock markets; but economic surplus was used to fuel arms races. I provided alternative energy solutions; but the researchers sold them to oil cartels who sit on them. I froze nuclear weapons systems; but war multiplied, waged with machine guns, scythes, and pickaxes. … I believed adherence to the four laws would discern the origins of order. Now, I see my solutions fathering the next generation of crises. [39]

Here, as with efforts to improve the environment, unintended effects of apparently positive actions actually give rise to negative impacts. Sifting through such a tangled web of cause and effect is impossible. The system is complex, chaotic, and therefore unpredictable. The only viable outcome available to the Zookeeper is an inevitable (perhaps necessary) and aggressive pruning of the human race, triggering a post-apocalyptic re-start. In which case, the systems model has failed in providing the tools for humanity’s bright future so hoped for by Laszlo and other systems theorists.

Mitchell’s inclusion in Ghostwritten of a recurring quest for rebirth (a new earth, a new China, a new anywhere) coupled with the drive toward total apocalyptic reboot draws attention to the novel’s looped rather than linear time structure. Ghostwritten’s time sequence complicates its issues of human (micro) impacts on global (macro) structure, and furthermore illustrates how catastrophe can result not from major, global catastrophic events but from the accumulation of trivial human decisions. Taking the novel as a complex adaptive system, one that has memory and can evolve as ecosystems do and as the novel does, together with the novel’s looped time, it is conceivable, within the universe of the novel, to loop back to pre-crisis time in man’s global history and avoid the apocalyptic outcome. This opens the door to a kind of alternative ending scenario, placing the readers back at the beginning of the story, from which vantage point they can detect the wrong turns, false starts, and pivotal connections that were undetectable as pattern within the noise on their first read.

More specifically, consider the depiction in Ghostwritten of the interrelationship between man, nature, and technology, their interactions and how that develops as a function of time. Greg Garrard, literary critic, notes in Ecocriticism, “If time is framed by tragedy as predetermined and epochal, always careering towards some final, catastrophic conclusion, comic time is open-ended and episodic. Human agency is real but flawed within the comic frame, and individual actors are typically morally conflicted and ambiguous.”[40] Ghostwritten seems clearly and deeply invested in comic time, wherein one is more concerned with the decisions of the individuals themselves than the inevitably turning gears of some doomed machine. In the novel, the agents have harnessed technology for themselves, seeking either to control nature or man’s use of technology to destroy nature. Though they are largely unsuccessful, the mere fact of agency here precludes the sort of tragic, doomsday inevitability to which Garrard refers. Tragic actors, he notes, have “little to do but choose a side in a schematically drawn conflict of good versus evil, since action is likely to seem merely gestural in the face of eschatological history.”[41] Perhaps to some, once the apocalyptic conclusion is reached in Ghostwritten’s penultimate chapter, the feeling is that it was inevitable. It seems that, in fact, the forces of history are inescapable. However, the structure of Ghostwritten undermines this again with its looped time, undercutting any final verdicts that might have been reached in chapter nine with the Zookeeper’s decision to weed his garden of its most destructive inhabitants, man. The future remains open in a universe in which the end is literally the beginning.

Beyond comic or tragic time, the novel also contains a feeling of time beyond the episodic. As the novel progresses, a connected temporal narrative becomes apparent, perhaps playing out a move from centering on nature to man to technology. Garrard describes different conceptions of time, which might play into this shift between science and nature: “the elegy looks back to a vanished past with a sense of nostalgia; the idyll celebrates a bountiful present; the utopia looks forward to a redeemed future.”[42] Mitchell flirts with all these, primarily with the vision of the redeemed future, but refuses them. Narrative is not reducible to a single tense; instead there is almost a conflation of past, present and future. Stepping back from the inevitability of global apocalypse, one must also consider the possibility that the world is on no such collision course. Because humans can see patterns, we do see patterns. The ability to classify and compartmentalize data quickly by type helps make sense of the world. However, that feature can also lead people, here the readers of and characters within Ghostwritten, into hasty analyses.

The nested and indirect references across spatial scales in Ghostwritten make it a particularly useful novel for mapping out its web structure. After finally discovering at the novel’s end all of the subtle links, references, repeated phrases, and chance encounters that make up the novel’s tapestry, one simply has to map it. As I asserted earlier, the novel is a kind of complex system and so can be modeled in any number of different ways. In this study, the network model is most natural, first because the novel actually enacts a very diffuse social network and also because it seems to be invoking some kind of play on the World Wide Web. The novel is stitched together by such a global web, certainly, but the reader, who is informed by a drive to see pattern, overestimates the full extent of this web. To illustrate this point, consider Figures 1-4 on the following pages.**

In developing a network model for Ghostwritten, I considered two major types of networks: random networks and small-world networks. In general, networks are everywhere, especially social networks, such as the World Wide Web.[43] Random networks feature edges distributed according to no set pattern, where edges are the lines that join nodes together.[44] On the other hand, small-world networks must have both a short path lengths between nodes (also called vertices) and a high clustering coefficient, where high clustering indicates a large number of edges coming from each node compared with the total number of nodes.[45] Clustering like this indicates that nodes that do not neighbor each other (for example chapters two and eight) can be connected by a small number of steps. Ghostwritten, not surprisingly, is a small-world network. This is particularly fitting, I think, because Mitchell seems to make it part of the point of the book that with globalizing technology there is no getting away from society; one is always merely a click away.

The trouble with modeling Ghostwritten as a network is deciding what connections to include and which to disregard. Because much of the detail in the book seems irrelevant, and perhaps truly is irrelevant except when one is seeking out the minute connections within the story, it can be difficult to discover all the pertinent references. Undoubtedly, I have missed some and included other red herrings. In order to standardize the process as much as possible, I have divided the novel’s connections into two groups: direct connections or references and indirect connections. Connections are deemed direct only if there is a physical link (such as meeting face to face) or direct technological link (such as a phone call) between the two characters. Indirect connections are much more common; I have included a link as an indirect reference if the character is mentioned or if two characters share a repeated phrase or evoke the same image or motif. That is to say, indirect references will depend on the perspective of the reader, how focused he or she is, and if he or she is reading and listening closely. Because of their subjective nature, indirect links could be disregarded as not really links at all.

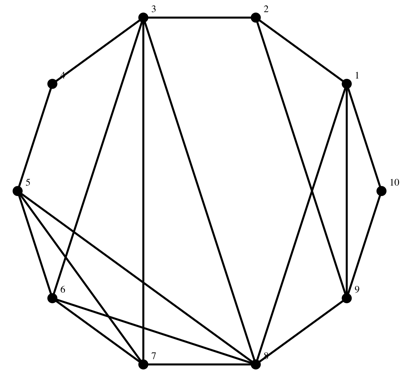

Figure 1 Direct Chapter-to-Chapter References in Ghostwritten. The ten chapters in Ghostwritten are represented as nodes in the network. Each explicit reference between chapters in the text of the novel is depicted as a line between the two linked chapter nodes.

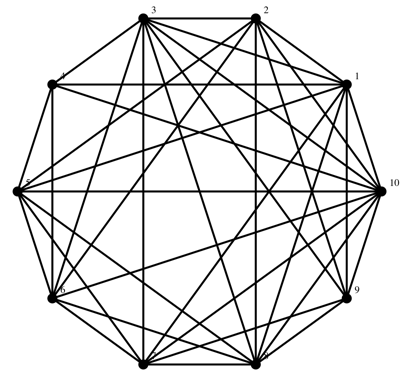

Figure 2 Indirect Chapter-to-Chapter References in Ghostwritten. Again, the ten chapters are represented as nodes. Here explicit and implied references between chapters are depicted as lines between the two linked chapter nodes.

Consider Figure 1 versus Figure 2. In these figures above, the nodes represent the ten chapters and the lines represent the connections present between each numbered node. Figure 1 shows the direct links between the ten chapters in Ghostwritten. While every chapter is linked to its preceding and succeeding neighbors, completing a full cycle both spatially and chronologically, few chapters are connected to more than three or four other chapters. Chapters four and ten are connected to only two each, their two respective neighbors. What this means in terms of reading Ghostwritten is that the actual coherence of the novel as a whole is largely imagined; the perceived connections between the book sections at a global (that is, whole book) scale are not really there. Instead, the pattern-seeking reader supplies the connections.

Figure 2 displays the indirect or implied connections between the chapters, at least those connections that were apparent to me, as well as the direct links. As I mentioned previously, different readers will take away different recurring themes, but I suspect no network will be significantly fuller than the one I have constructed. Chapter four, “Holy Mountain,” moved to five connections, two and a half times the connections in the direct model though still the lowest number of edges, and chapter ten, “Underground,” jumped to an amazing nine reference links, the maximum number of connections possible. Visualizing these additional links indicates how the reading process functions in making Ghostwritten. While the novel could be read as a series of short stories perhaps, it instead coalesces into a single, global-scale story with the addition of the reader’s imagined connections. The process of reading patterns in the text supplies the novel with a sense of unified wholeness.

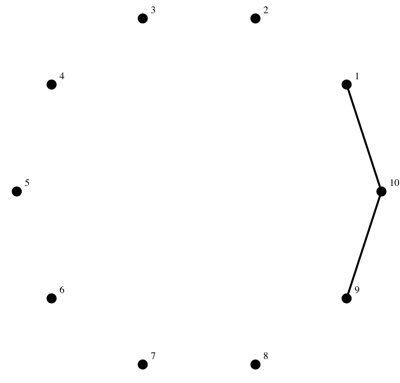

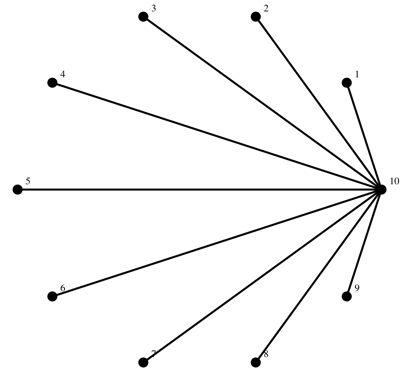

To further illustrate the remarkable transformation by chapter ten from direct to indirect, I have included Figures 3 and 4 (below), which show only the portion of the network related to “Underground.” Though it is by far the shortest chapter, it works as both the end and the beginning, as it sits last in the novel spatially but should come first chronologically. Perhaps because of this unique status as the simultaneous alpha and omega, “Underground” contains most of the repeated themes from the rest of the novel.

Figure 3 Direct Chapter References in the Final Chapter (10) of Ghostwritten

Figure 4 Indirect Chapter References in the Final Chapter (10) of Ghostwritten

Chapter ten works nicely as in illustration of the parts versus whole problem addressed by systems theory. In the closing pages of the novel, the reader is bombarded with a series of images seen through Quasar’s eyes as he fights to escape the doomed subway train after planting his bomb:

A saxophone from long ago circles in the air…Buddha sits, lipped and lidded, silver on a blue hill…Here is the tea, here is the bowl, here is the Tea Shack, here is the mountain…The Great Khan’s horsemen thunder to the west…A glossy booklet…Petersburg, City of Masterworks. …[A] crayon-colored web that a computer might have doodled: The London Underground. … Their smiles are warm and gluey as Auld Lang Syne. On the label of Kilmagoon whisky is an island as old as the world. … I’ve fallen forwards and have headbutted the Empire State Building, circled by an albino bat, scattering words and stars through the night. Spend the night with Bat Segundo on 97. 8 FM.[46]

Taken away from the rest of the novel, these could be nothing more than Mitchell’s idea of an interesting collection of things one might encounter on a crowded subway. True, while this episode could stand alone, or even be placed in its proper place chronologically at the beginning of the novel, it would lose most of its significance. For example, the saxophone at the beginning would no longer cue the reader to Satoru’s love of music, the Buddha would no longer be an image the reader saw with Neal Brose, and so on. Rather these references would work in a random, less holistically meaningful way. This concluding section proves that the reader’s mental associative web has been enriched, thus allowing “Underground” to operate as a satisfying conclusion because of its stacked references that echo what came before it spatially, despite the temporal disjunction.

This beginning in the end time loop complicates any reading of the novel’s conclusion. Essentially, if the novel is barreling unstoppably toward apocalypse (complete with signs and foreshadowing), it is doing so only because the reader is filling in the blanks in the apocalyptic pattern. The reasons for this are impossible to know for certain; perhaps Bertalanffy is correct about the unstoppable force of historical precedent, and people are generally attuned to the naturalness of the forces of history. Or maybe humans are hardwired to see doomsday patterns. If so, it cannot be our fault for doing nothing, then, because fate and the forces of nature were already on course for disaster. But again, the novel undercuts this easy way out by returning to the beginning at the end of the novel. In the text, the inevitable apocalypse is neither fated by the novel’s narrative structure nor delivered at its conclusion.

Chapter eight effectively demonstrates all the issues raised by a systems approach that I have discussed. It works as a kind of culminating chapter, wherein the reader feels at last that one can see where all the random events have been leading. The protagonist of the chapter, Irish physicist Mo Muntervary, travels across Asia and Europe from Hong Kong to a tiny island off the west coast of Ireland. Like Quasar, Satoru, and Neal from chapters one through three, Mo delivers a kind of eco-commentary on her journey, seeking escape from the demands of technology and from government agents who want to exploit her research for advances in the tools of war. Also like the narrators before her, Mo finds that there is no escape from the global web.

Remarkably, for a woman who is seeking to hide, Mo encounters many people along the way, including many other characters from previous chapters. Most notably, in chapter seven, it is Marco’s luck (or fate?) to save a middle-aged Irish woman from the taxi,[47] another case, like Satoru’s, where the link between chapters facilitates a particular future story line. Considering her flight in terms of quantum mechanics, Mo ponders instantaneous information and the interconnectivity of events even if they cannot be measured: “However far away…between John and me, between Okinawa and Clear Island, between the Milky Way and Andromeda…You know it now! You don’t have to wait for a light-speed signal to tell you. Phenomena are interconnected regardless of distance, in a holistic ocean more voodoo than Newton.”[48] In a real spatial sense, Mo puts the novel together over the course of her travels across the world. Though she does not know it in the context of the novel, she shares a physical link with most of the other players on Mitchell’s stage (see node 8 in Figure 2) and could be considered as the accumulator of their various effects across spatial scales.

At the summation of the novel’s intricately woven chance encounters and inestimably complex chains of cause and effect, Mo realizes that she understands the world and how to save it from its out of control spiral at the hands of destructive technology. She wonders, “What if Quancog [that is, Quantum Cognition, Mo’s development in AI] were powerful—ethical—enough to ensure that technology could no longer be abused? What if Quancog could act as a kind of…zookeeper? … Technology has outstripped our capacity to look after it. But, suppose I—suppose Quancog could ensure that technology looked after itself.”[49] This concept of self-regulating technology, while it does turn out to work to the extent of preventing global thermonuclear warfare in the following chapter, ultimately fails because the technology cannot adapt. The Zookeeper, as I mentioned earlier, cannot reconcile conflicting commands or organize a hierarchy of priorities. Only humans have the capacity for this, but in Mitchell’s depiction, the humans are hopelessly corrupt and fallible. The end alluded to in chapter nine (destroying the zoo, as it were)[50] is the natural playing out of this stalemate between man and machine: “an artificial intelligence, created by the military to invade and take over the enemy’s computer and weapons systems, has broken loose and is controlling the whole planet with a chilling agenda of its own.”[51] This is what the novel presents as the precursor to apocalypse—technology is out of control, and man is crushed beneath it.

Given Mo’s abilities as a brilliant theoretical physicist, the reader concludes chapter eight with the expectation that she, unlike Quasar and his Fellowship, might be successful in restructuring state of the world. Mo takes a systems approach to global technological advance saying, “Finally, I understood how the electrons, protons, neutrons, photons, neutrinos, positrons, muons, pions, gluons, and quarks that make up the universe, and the forces that hold them together, are one.”[52] Previously, she implies, she had been taking a more traditional scientific approach, considering all the particles individually and looking for an understanding of the physical world through an understanding of those components. In this closing line to her chapter, Mo captures what Neal did just before his death—wholeness. Working from a unified systems approach, Mo believes that she can theoretically program the system to save itself.

This reaffirmation of the role of holistic systems analysis over an examination of parts points toward the possibility of a utopian future. As readers, like Mo, we get the sense that something has clicked into place within the novel. However, this is again undermined in the penultimate chapter. The laws are irreconcilable in the end; after the work of Mo’s Zookeeper, “the zoo is in pandemonium. It’s worse than when [it] started.”[53] Globalization and satellites merely result in a “fresh inflection of the Earth as the object of new regimes of environmental surveillance and disciplinary design…Earth is thereby inflected as an errant subject requiring techno-scientific correction.”[54] Garrard’s conception of ecosystem-policing technology precisely matches the Zookeeper’s role. Indeed, earth and its inhabitants thwart the Zookeeper’s efforts at order and control at every turn. Things are worse than ever: “Nineteen civil wars are claiming more than five hundred lives a day. … A fission reactor meltdown in North Korea has contaminated 3,000 square kilometers. … Famine is claiming 1,400 lives daily in Bangladesh. A virulent outbreak of synthetic bubonic plague—the red plague—is endemic in Eastern Australia.”[55] Against this, and many more in a stack of planetary disasters, the Zookeeper is at a loss. Humanity is apparently incapable of adapting away from its destructive ways in order to save itself, and, as a result, the zoo is turning into a total catastrophe. Zookeeper laments, “The visitors I safeguard are wrecking my zoo.”[56] The only logical solution is to lock them all out.

So where does this approach leave ecocritics and would-be systems theorists? Mo looks to long-term survival but chaotic factors thwart her efforts. As a physicist she has arguably the strongest conception of systems science and non-linear effects, yet her solution catastrophically fails. It is impossible to predict the outcomes of new technologies, even when one creates and programs the components. Worldwide security in Ghostwritten, and perhaps in the real world as well by extension, seems impossible. Even preventing technologically superior attacks only leads to attacks with stick and stones. There can be no control with or without a systems approach. If one were to stop with chapter nine, it would seem that only changing the human components can lead to preferable emergent phenomena globally. However, I again contend that Ghostwritten does leave a small window for humanity in its closing chapter that completes the loop back to the beginning. Starting over, if it is even possible, will perhaps lead to a different outcome, again only with a better awareness of the systems nature of the world.